i keep seeing this tweet

so this tweet has been on my feed for quite a while now

at first i was thinking about doing all of this on my own, but after some research i was too lazy. so i’ll just do a quick analysis on how it works and on what it actually does.

benjojo, the guy behind the project, also did a blogpost about the project

what is a DNS?

DNS are the base for everything that we know on the internet even if most people don’t even know it exists. almost everything we can access on the web is going through a DNS name. the goal of a DNS is to create a link between a domain name and an IP. the concept of domain names and DNS is getting a little old now, the first RFC about DNS was published in November 1987.

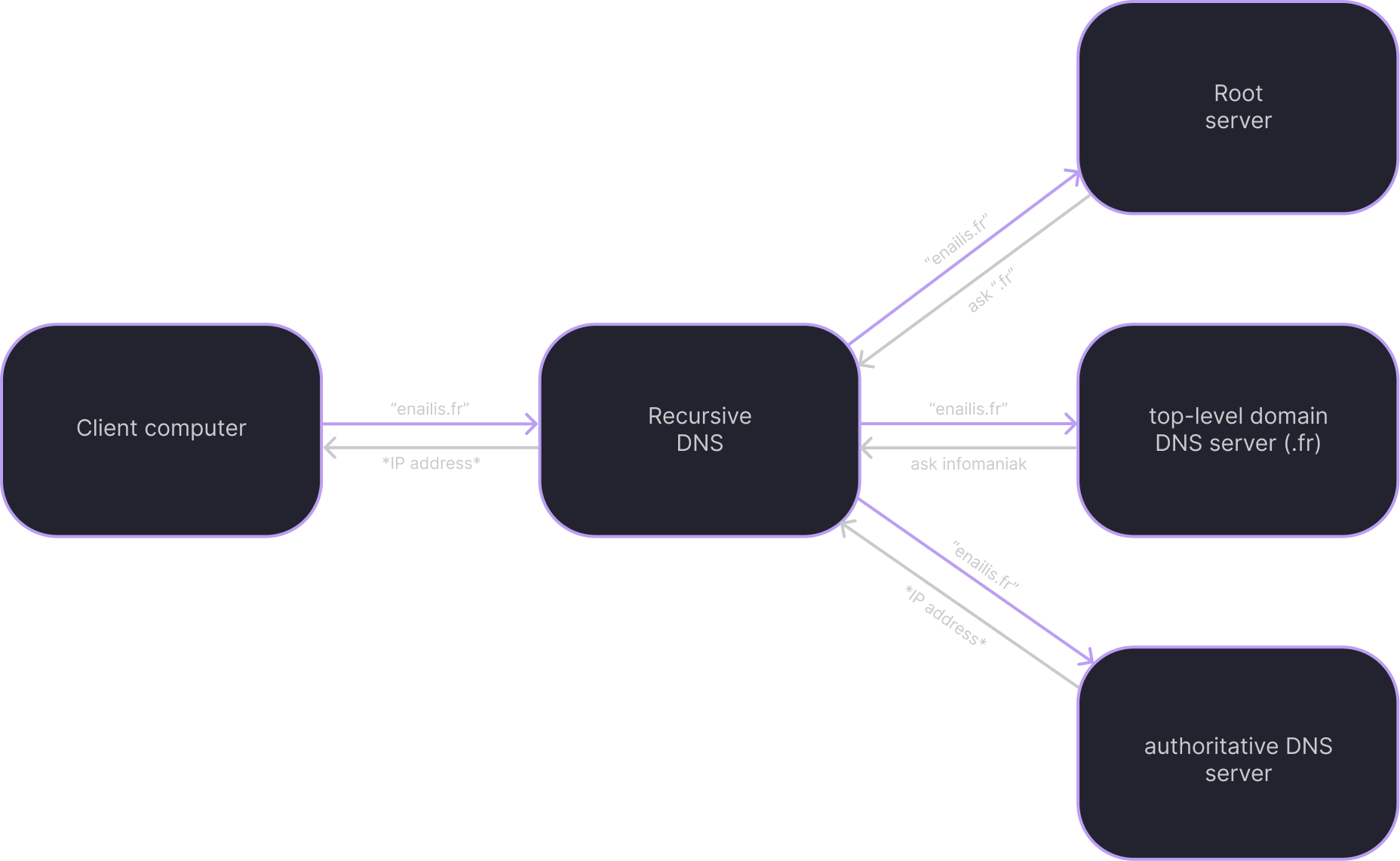

there’s 2 main kinds of DNS: recursive DNS and root DNS

recursive DNS

this is the DNS your browser first contacts. there’s hundreds and thousands of them around the world. you probably know some of them like 1.1.1.1 from CloudFlare, 8.8.8.8 from Google or 9.9.9.9 from Quad9. most people don’t really care about what DNS provider they use and let their ISP chose for them.

everytime you search for something on the internet your browser asks “do you know the IP of that domain name?” to the DNS, to which he most of the time answer “nope” but what makes them special is that they know where to find them.

root DNS (a kind of authoritative DNS)

kinda like a phone directory, the root servers (and authoritative DNS) have a dictionary that matches domain names with IP addresses within a define region. once the recursive DNS has made its request, the root server will redirect it towards the top level domain DNS server that will redirect towards the authoritative DNS server. for example for accessing my website, this is what happens:

how can you store anything in a DNS?

the RFC from 1987 talks briefly about why and how a cache system was implemented in the DNS. to put it simply: we don’t want to make an infinite number of query so we cache some of them for a predefined amount of time. since people love parasitic computing, this way of working has been used to do some other things like temporary storage like DNSFS for example. this is not the first time that a network thingy has been used as a file system, a few years ago yarrick published pingfs which is essentially the same thing but using the ping system.

find the DNS

the first thing to do is get the list of all available DNS. most of them are firewalled off from the public internet for reasons i won’t detail here but some of them are misconfigured which allows to use their resolvers. in total there’s around 4.3 billion IPv4 but if we remove the unreachable IPs defined by the RFC 1918 and the IPs that don’t want to be scanned we’re down to around 4 billion IPv4 which is still gigantic but doable.

to scan them all, we need to be able to scan for open resolvers (so something that reply to port 53 on UDP) but it needs to be a DNS that can look up for domain names, not an authoritative DNS. to do so, i’ll be using masscan. to be sure that my queries give me exactly what i want i’ll look at the response from them and only accept answers from a DNS with authoritative answer set to something else than 1.

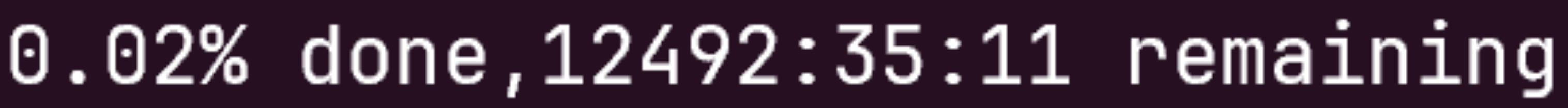

i then created a BPF rule that i inserted into my iptables. this is an easy way to filter any traffic i don’t want. i then was able to use masscan to go through the whole internet and find what i was looking for. it was very long…

in total, i’ve found around 4 millions open DNS. almost half of them are in China which is not that surprising.

but can they store data?

every DNS can store data but most of them don’t store it for a long time. the easiest way to find out which DNS can store data the longest is by storing a TXT record with the longest TTL possible (2147483647 seconds so around 68 years, first defined in RFC1034 but changed in RFC2181) and to check every hour if it’s still there.

after doing this i had ~350.000 resolvers that could store data for 21h in average. most of them were DNSMasq, then Microsoft, BIND, PowerDNS, Nominum and ZyWall. all of them have a different amount of cache listed here:

| DNS Provider | Cache size |

|---|---|

| BIND | 10MB |

| DNSMasq | last 150 entries |

| Microsoft | it’s weird so idk |

| PowerDNS | 2MB |

| Nominum | idk |

| ZyWall | idk |

let’s look at the code

now that we know all of this, we need to setup a way to make all of this work. and by “we“, i mean benjojo. looking at the code of DNSFS we can see that we found almost the same results about the DNS servers.

how is that data stored?

the first thing we can see it that benjojo decided to split the data into 180 byte chunks:

1 | chunkcount := len(fullfile) / 180 |

he also made it so the storage is kinda stable. the TXT records are replicated on 3 different resolvers:

1 | for replications := 0; replications < 3; replications++ { |

following that logic, we can deduce that, with the number of DNS i have scanned and that can be used, we would have ~200MB available.

how is it sent?

the code to send data to resolvers is very simple:

- split the input file into 180 byte chunks of base64

- send those chunks to multiple DNS as TXT records

- delete the input file (from DNSFS memory)

benjojo created the function below to spread the data evenly on the resolvers. he achieved this by hashing the name and the number of chunks of the file uploaded and modulating it to the resolver list.

1 | func getDNSserverShard(filename string, chunk int, copy int) (IP string, query string) { |

how is it fetched?

the fetch part of DNSFS is straightforward. when you upload a file, you give it a name, so fetching is just searching for the corresponding chunks.

1 | filename := req.URL.Query().Get("name") |

the fetchFromShard function is just getting the byte chunks from resolvers. and everything is writen into an output file.

conclusion

even if resolvers are not meant to be used that way, it is possible to store on them using their cache system. this way of storing data is absurd: it can store only ~200MB and it’s very slow.

analysing DNSFS and working on this article was just a fun way to learn more about how resolvers work.